Extraordinary, the wisdom to junk the average: Brand Matters

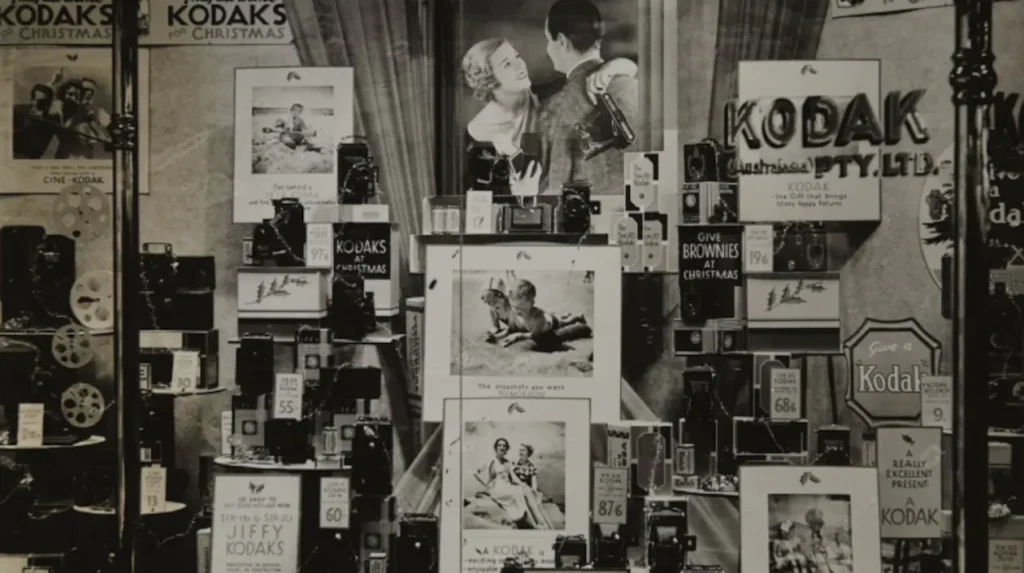

It is true that ‘what gets measured gets managed’, but the concurrent truism is ‘what gets averaged gets mismeasured’, writes Shubhranshu Singh [siteorigin_widget class=”SiteOrigin_Widget_Image_Widget”][/siteorigin_widget] A bespoke suit from say, Henry Poole & Co, Saville row, London costs anywhere from INR three to five lakh A top-of-the-line fighter aircraft such as the Lockheed Martin F-35B or the Dassault Rafale, costs about Rs ten billion each. A bespoke suit from say, Henry Poole & Co, Saville row, London costs anywhere from three to five hundred thousand rupees. It takes a minimum of three to four sittings. There is a three-month cycle for getting a suit turned out. First basted fitting maybe six weeks after measurement followed by a forward fitting a month after that to make the suit. To start with, one must take an appointment and have a conversation. In contrast, the fighter aircraft’s fittings and cockpit are designed for the average man’s bodily dimensions. However, there is no such thing as an average human hand or an average human body. That we call average is merely a narrower range of dimensions. When you design a cockpit for an average man you were designing a cockpit not for everyone. Why is the world of technology, design and marketing besotted with ‘the average man’? It is because all business metrics, and especially averages, look to the middle of a market and that’s how the bell curve pans out as well. In volumetric terms for doing ‘business as usual’ we are well advised to stick to the average. But this will not suffice for game changing work. Innovation happens at the extremes. You are more likely to come up with a good idea from the ends of the range than from its central casting. Consumers who are out of the ‘expectation range’, present more opportunities to understand factors for acceleration as well as the barriers to growth. A comfort with the average suggests lack of intellectual exertion, mental comfort, incrementalism and even, smugness. Perhaps, by this measure, traditional market research may have dismissed more good ideas than it has originated simply because of its search for the representative average. It is true that ‘what gets measured gets managed’, but the concurrent truism is ‘what gets averaged gets mismeasured’. If everybody is conditioned to pursue the same narrow goal, in the same narrow way they end up assessing their results in a similarly narrow way. The choices made using average criteria cannot bring out the full spectrum business reality to light. Arthur Lewis won the Nobel Memorial Prize for Economics. His 1941 paper on “two-part tariffs” for a business requiring customers to pay an entry fee to gain access to products they then pay for the actual product or service. This brings out the question of how wide bracket is a definition of the average here? Economist Walter Oi authored a paper “The Disneyland Dilemma,” on the theoretical conditions for when it made sense for the amusement park to charge guests an entry fee as well as separate fees for every ride—or in other words, whether the revenue from the additional tariff was worth losing those customers unable or unwilling to pay the additional cost of entry. In the end, Disney opted for just the one tariff. In semi-monopolistic micro-markets like Disneyland, food, souvenirs, and other offerings function as a profitable second tariff. Ever been thirsty at an airport terminal? You will know that businesses can get away with exploitative pricing in situations where consumers have no other readily accessible options. It will hardly qualify as a story for the average mapping of the consumer reality. The dharma for a marketer is knowing their audience. If a brand builder does not truly understand the different types of people being served, how is it to be determined who will respond to a product, service, or intervention at scale? Always think “How broadly will the idea work?” Brands travel across cultures, climates, geographies, and socioeconomic groups and will inevitably meet vastly different realities than in the preparatory pilots. To truly achieve widespread impact, a brand owner needs to also think about how the current consumers might differ from the future ones. The initial audience, test population, or test market segment—that yielded your early success may not be a representative snapshot of the larger group of people needed to make your brand a success. Look for biases, homogeneity, and myopic representation of population. Fitness enthusiasts will be the ones looking for a gym. No genius required there. But does the brand that is looking to be in the fitness business serve the core? Or is it about a non -enthusiast segment? How are gym plans being priced? With which segment in mind? Looking at the typical average can distort results. All marketers encounter the “selection effect” whereby test results are way more positive than the actual subsequent scale achieved. Regular gym goers are more motivated to improve their health and may dine at eateries with a healthier menu of options. They may consciously manage stress better. In these cases, you might incorrectly attribute improved health outcomes to the gym visits rather than the other healthy habits that such enthusiasts will inevitably have. This is the false positive we must be careful of. The case of the ‘New Coke’ disaster has now passed into marketing lore. In the mid-1990s, McDonald’s did extensive focus-group testing on a new item – the Arch Deluxe that turned out to be a deluxe failure. It happened because the people who participated in the focus groups weren’t a faithful reflection of McDonald’s customers. The burger enthusiasts who participated were an ‘average’ of McD’s core but the average person in the larger population went to simply get a Big Mac. Your initial audience may not be representative of the population of interest. These challenges have even shaken the foundations of social science, on any claims to universal findings about human nature. Joseph Henrich, an anthropologist did research in Peru with an indigenous Amazonian

Extraordinary, the wisdom to junk the average: Brand Matters Read More »