Ask ChatGPT, how to build great brands from buzzy innovations

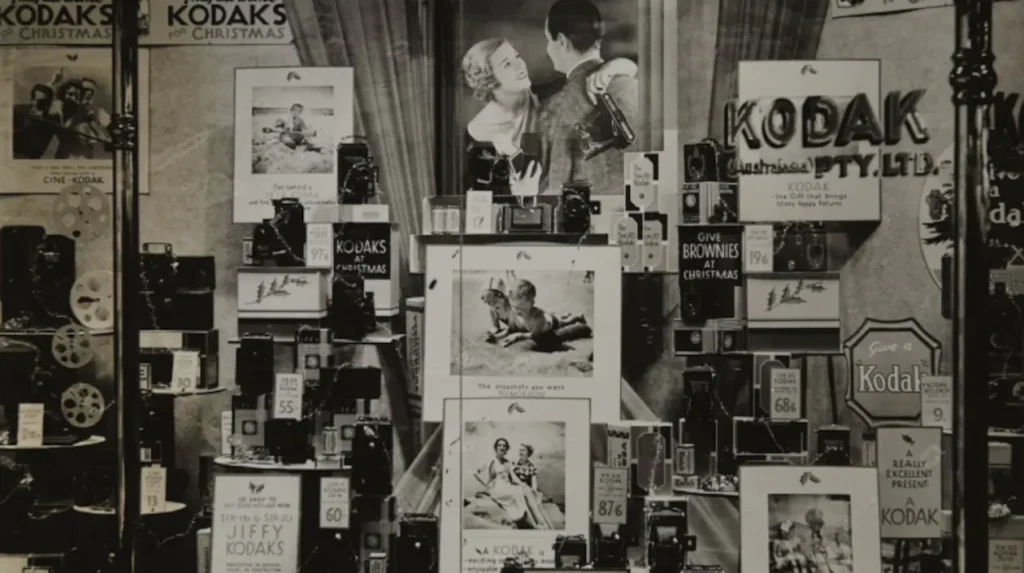

Hold on. You don’t need a chatbot for it. We have it covered for you. In this week’s Simply Speaking, understand why savvy marketing is perhaps even more important than game-changing innovations. [siteorigin_widget class=”SiteOrigin_Widget_Image_Widget”][/siteorigin_widget] In the Internet age, markets have been addressed in a state of fragmentation into various segments and niches. Customer networks emerged and its members influenced each other’s choices reciprocally. Traditional one-way communication—inform, persuade, and convince to buy – has been replaced with nuanced approaches where consumers themselves decide the main influencer. (Representative Image: Kyle Glenn via Unsplash) “The two most important functions of a business are innovation and marketing” – Peter Drucker A new sun has risen in the world of tech innovations. ChatGPT has the potential to change the world in many ways, impacting jobs and transforming industries. Its ability to understand and generate human language could be used to improve the capabilities of a wide range of AI-powered systems, including virtual assistants, chatbots, and other types of natural language interfaces. This could make it easier for businesses to interact with customers and for individuals to access information. In different fields such as customer service, content creation, search, information retrieval and education, ChatGPT is set to transform the world. While it’s important to note that the model is still new and that there are ethical and societal implications that need to be considered, the potential benefits of ChatGPT are hard to ignore. Google, Meta, Amazon, several start-ups are taking on this ‘open AI + Microsoft’ combine. It is not going to be an uncontested road ahead. Is this change truly shape shifting and immutable? Is it merely evolution with more fizz? What lessons can be learned from brand building of innovations? It is a proven fact that great ideas die in labs and proving grounds because a viable means to commercialise them does not emerge. When the lucky few do make it to the marketplace, getting awareness and due consideration is a steep hill to climb. Then there is the need to be able to present a product with due context. It is like looking into a mirror. Too close and you can’t see the full picture and too far away, you cannot see clearly enough. In a similar way, market immersion needs to be optimised and done iteratively. Innovations driven by a new technology, typically follow a multi phased marketing process. As soon as a new technology emerges, it is initially used by experts and technology enthusiasts. As it begins to spread, new companies most open to innovation in marketing come into the market. At this time the majority adoption has also occurred. The earlier technology now begins to be commonly used. A stage is again set for innovation. This cycle repeats itself with shorter and shorter time frames. Three ‘laws’ can explain this new world. The first is the ‘Moore’s Law’ of exponential growth and ever lower costs of computer power. The second is ‘Metcalfe’s Law’ about the value of networks, which grows disproportionally to accretion in size, and the third ‘Gilder’s Law’ is that the total bandwidth of communication systems triples every twelve months. The business model of the mechanical age (and the first phases of the electronic age) was based on the creation of efficiency through economies of scale in production and economies of scope in distribution. In the Internet age, markets have been addressed in a state of fragmentation into various segments and niches. Customer networks emerged and its members influenced each other’s choices reciprocally. Traditional one-way communication—inform, persuade, and convince to buy – has been replaced with nuanced approaches where consumers themselves decide the main influencer. Innovations are evaluated differently now than before. People are better informed, interact faster, and act faster. As the customer network gains weight, its influence on the reputation of the brand needs to be reconsidered periodically because effectiveness can decrease when buyers belong to new generations. In my opinion, the growth of artificial intelligence-driven algorithms and predictive analytics have heightened the need for more expertise and ‘true to domain’ marketing rather than lessen it. Marketing is deliberately cramped in most ‘routine’ decision making. Sales metrics are often used to evaluate brand building. The reverse is often ignored. In other words, brand health surge, a lead variable, may get ignored when compared to a surging sales performance which may well be on the back of promotions and tactics that in fact damage the brand. The search, content, and loyalty campaigns that get called marketing are mostly only shallow tactics. True brand magic is up the value chain – in ideas, insights, product origination or indeed, creating markets. Any cheaper alternative can be found for boring copy or visual rendition. You hardly need ChatGPT. Understanding people’s fundamental needs and drivers, identifying customers, and developing the entire go-to-market and usage ecosystem decide the success of innovations, especially breakthrough ones. Marketers need to be included in development discussions upstream in the innovation development process. Besides clearly defining who to sell the new offering to and how to sell it, such involvement helps in the following ways: Exploration of consumer needs and framing of insights – Marketing must probe deeper than the consumer has thought about the need. It must dive into the subconscious. Unstated needs are the best sources of value creating innovations. Creation of product or service appeal based on relevance and context – The context is about the cultural, social, and psychological levers that elevate an innovation to an instant or enduring hit. Walking in consumer shoes – Done via customer research and insight development, it bleeds into communications framing and marketing must ensure genuine consumer utility is obvious. Thinking of entire ecosystems – Innovations today rely on several partners and involves others outside organisational boundaries directly and indirectly. Going solo may often be detrimental to rapid brand establishment. The recent past has several examples – Blackberry, Electronic diary, Pager, Segway, Walkman, iPod, 3D printing, Blockchain, and Augmented Reality/Virtual Reality that succeeded, rose and then wasted the original scale of promise that was visualised or surrendered it to the

Ask ChatGPT, how to build great brands from buzzy innovations Read More »